This article is Part 4 in a 5-Part Series.

- Part 1 - Eris CLI Tool Walkabout: Services

- Part 2 - Eris CLI Services Walkabout: IPFS

- Part 3 - Eris CLI Services Walkabout: BTCD

- Part 4 - This Article

- Part 5 - Eris CLI Chains Walkabout: New

Docker is a bit of a strange cat for folks who are just getting up to speed. Many people when they’re getting started with Docker think of it in terms of a “Virtual Machine” as many are used to this idea of execution being constrained into a “virtualized” environment. The problem is that Docker is not a virtual machine. Indeed, it is a very different animal entirely than virtual machines.

Virtual machines are a mechanism to provide an isolated interface to a computer where the isolated interface runs an entire OS. That OS is booted from the start and then operates just as if it was the primary operating system on the machine although its “connection” to the hardware that exists on the computer is mediated by VirtualBox, VMWare, Xen or one of the other virtualization software suites.

The basic idea (and, for us, the appeal) of using both virtual machines and containers, is that programs are able to get started in a consistent manner. Because we are building eris to be runnable in a wide variety of situations from large cloud deployments to laptops and many iterations in between, we want to be able to provide users with a harmonized experience across those operating systems. This is an old goal in programming, but because of the large differences across operating systems and host environments there are approximately an infinite amount of edge cases which raise challenges for creating software. Were we a company the size of Microsoft or Oracle then I could tell the platform team to just build natively for each major operating system and be done with it. But we have four engineers at Eris. Yet building a system which can consistently run across a wide variety of host environments is possible because of what Docker and virtual machines offer us.

Docker is a “containerized” system where individual processes are isolated and given direct (unmediated) access to the Kernel according to the terms which Docker allows when a container is started. There is a lot of detail required to fully understand the difference between a full virtual machine and containers (some answers available here and here) but the basic way that I think about it is that containers are isolated processes running within a Linux operating system whereas virtual machines are isolated operating systems.

To summarize the links above, the major difference(s) between containers and virtual machines gets at what is actually “shared” between the host (or other containers) and the running executable inside the isolated environment. A virtual machine isolates the entire operating system. This means that virtual machine images are routinely 1-10GB large and each of them is unique (in other words the host must hold 1-10GB X however many VMs it is operating). On the other hand, Docker containers are built as minimal viable operating processes and as such are usually smaller in size. Containers are able to share a significant amount of their file structure across containers on a single host. But more importantly than having the actual images smaller is how the images are built. Docker builds its images in layers and when one does docker pull or docker push what Docker actually does behind the scenes is to reconcile each of these layers as individual layers. Docker also reuses parts of images across containers.

So what does this mean? At eris we build almost all of our core images as addendums to the eris/base image. The eris/base image is a jessie based image. It does no more than make sure that go is installed and have an eris user built. At the time of this writing, the eris/base image weighs in at 519.1MB.

To build data containers we have an eris/data image. This image is FROM eris/base and then it establishes a volume which will be used to store data from an operational container. The eris/data container is also 519.1MB. But when one downloads from Docker the eris/base image AND the eris/data image, one will not have to download 519.1MB X2 but rather 519.1MB X1. While it is not ideal that one would have to download 519.1MB at all, it is necessary to get going providing users with a harmonized, isolated environment for running distributed applications.

Compare this to the eris/ipfs image which is 572.7MB big. It is also built FROM eris/base so when a user downloads the eris/ipfs container, but already had downloaded the eris/base container, one will only have to download the extra layers which comprise only the ipfs executable and a small start script, or 52.6MB. Go binaries tend to be a bit bigger than other compiled languages because Go compiles the runtime into the binary. That said, 52.6MB is not that large for all the functionality one gets from the IPFS container.

Similarly, if one has downloaded the eris/ipfs image and wants to start it, by default eris will want also start a container based off of the eris/data image, but since the eris/data image and the eris/ipfs image are both FROM eris/base then there is not really anything (other than a simple establish the volume command) which docker will download when the eris/ipfs and eris/data images are used to start containers.

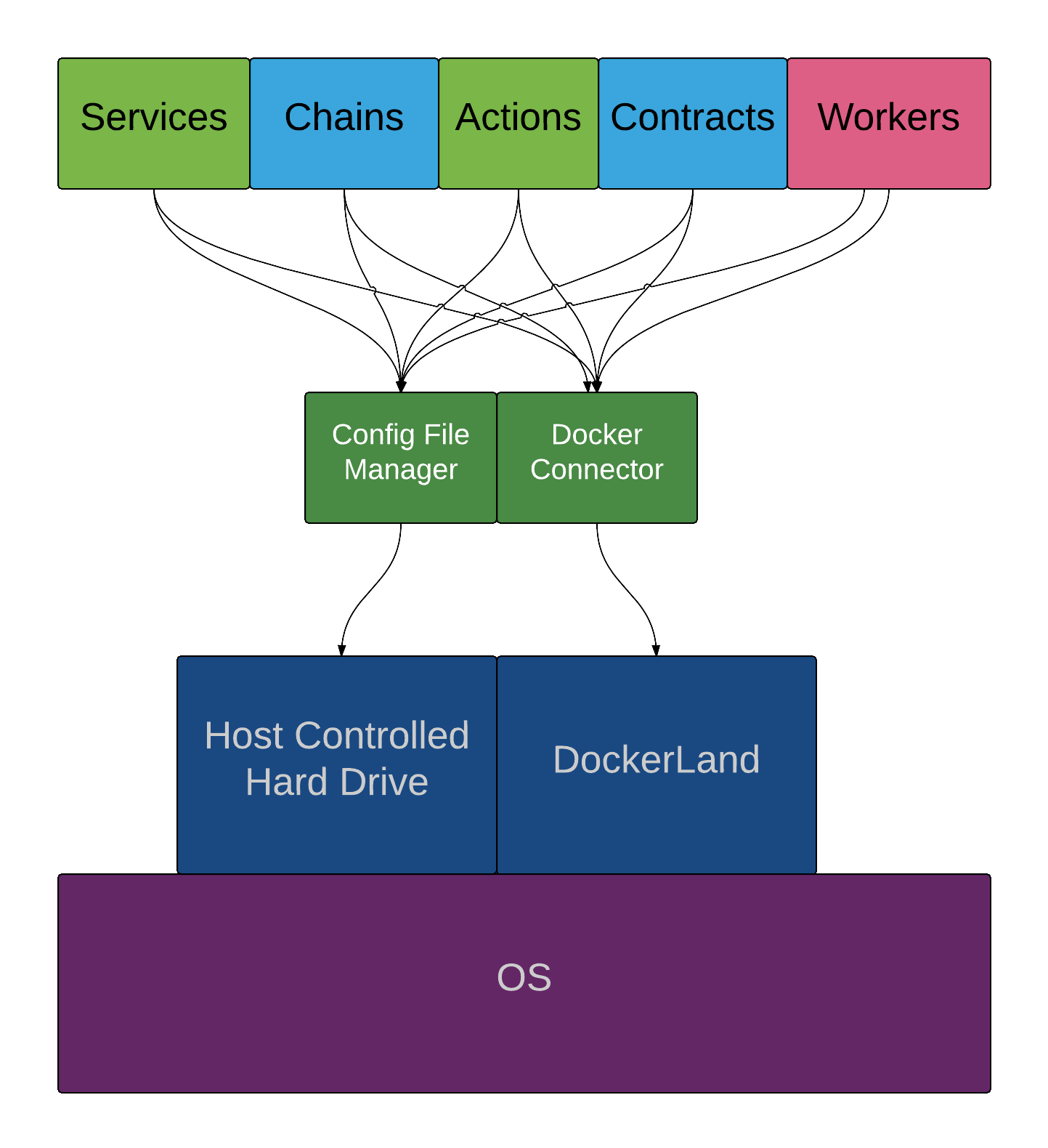

Right. So with that background in mind. How does Eris interact with Docker and how does Docker interact with the operating system. Let us first take a look at the overall operall design of eris the tool:

Eris connects to both a Host’s harddrive (usually in the ~/.eris directory is where we keep all of our files needed to run and interact with various distributed applications) as well as a Docker daemon. That Docker daemon then interacts with the (Linux only) operating system. To be a bit more precise what is happening looks like this:

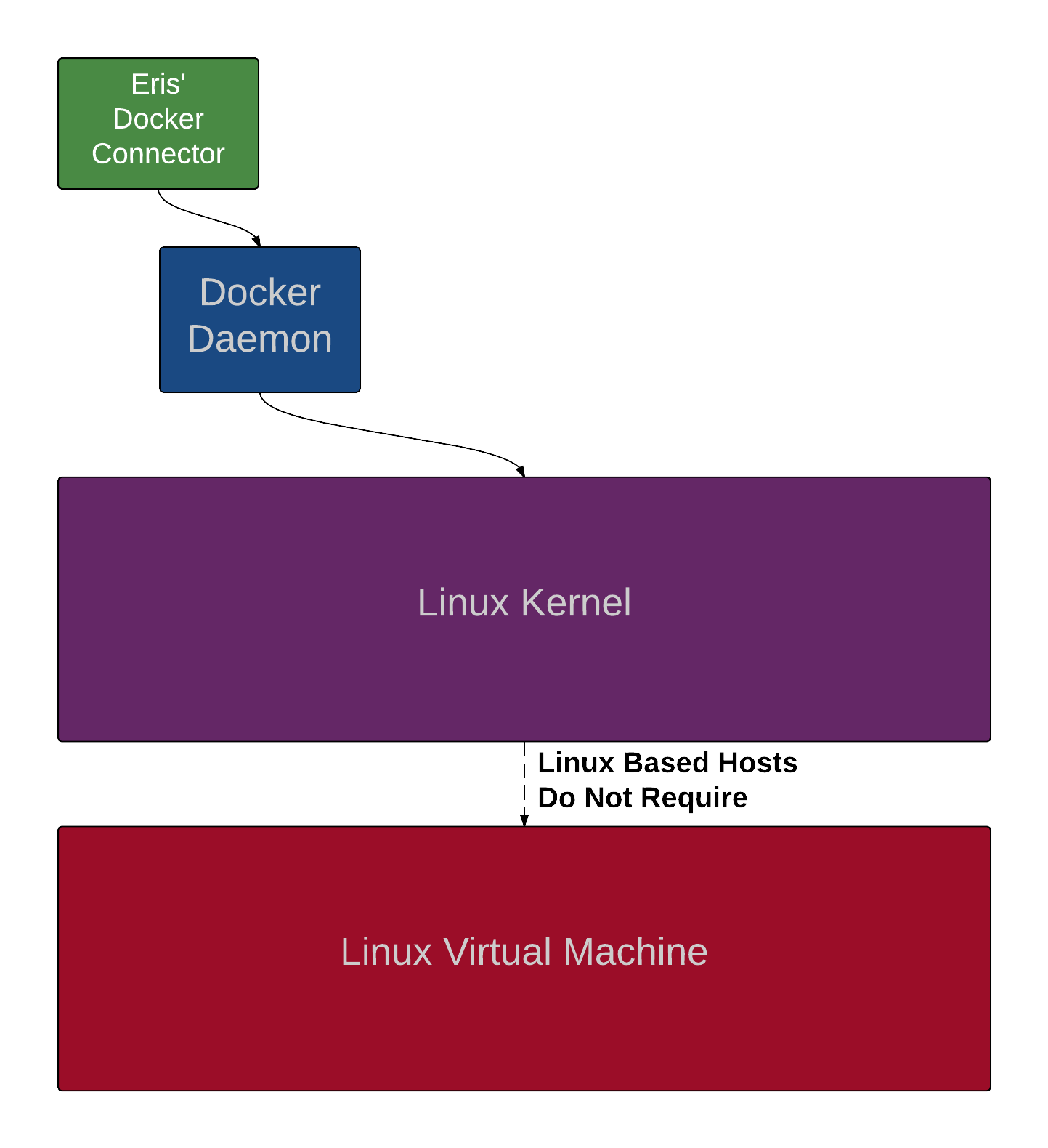

Docker is really only able to interact with a Linux kernel. This means that for users who are on Windows or OSX they will need to have a Linux based virtual machine with Docker attached to it. We strongly recommend to folks that they use the Docker Toolbox which will install everything needed to create Docker only virtual machines (which basically are just a Kernel and a Docker daemon and as such are very small and lightweight) on local or remote boxes. If users run Linux natively on the host running Docker in a virtual machine is fine as is running Docker on the host and connecting into the Daemon that way. Eris will connect to Docker either via an https connection if Docker is running in a virtual machine (whatever the host OS is) or over unix sockets if Docker is running on the Host.

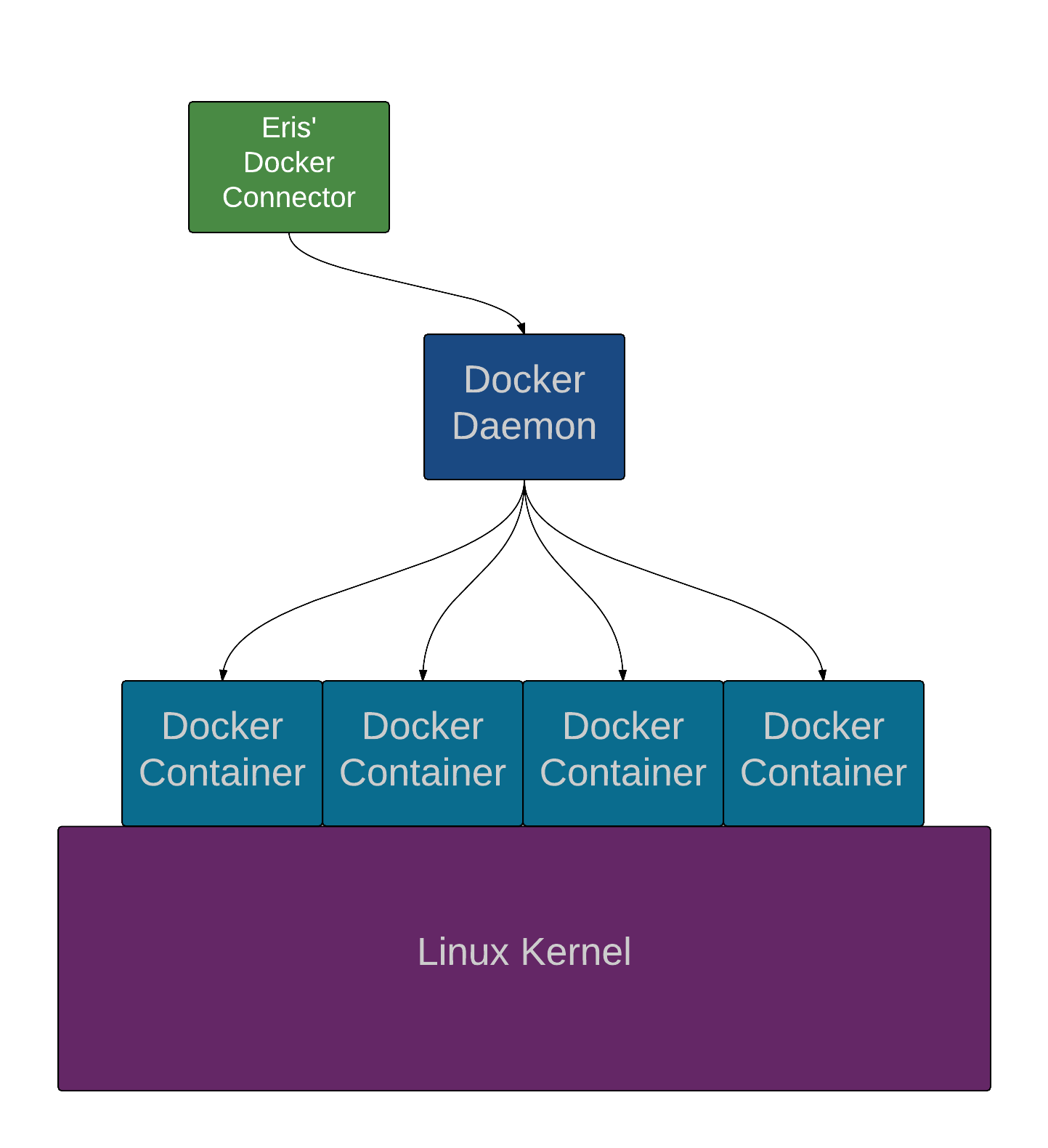

Finally, when this is all put together it looks something like this:

Of course the Linux Kernel in the above image may be running inside a very lightweight virtual machine or directly on the host, depending on how one is set up.

The other big learning curve for new users to Docker is the differences between images and containers. This is a bit easier to communicate so I’ve left it for the end. Docker images are immutable layers of files which define how an isolate process should run. Containers, on the other hand, are the running process itself. Containers, once started, cannot be “changed” in the sense of what ports they are given access to, what their starting sequence command is supposed to be etc. They can be stopped, started, paused, unpaused, etc. But they cannot change too much of what they can do other than their state in terms of being “on” or “off”. For example, to open a new port from the host to a container, one would have to remove the container and make a new container with a new process. Although with eris we are able to abstract most of this from the user via our service definition files paradigm along with eris services update).

Hope this has helped you understand a bit of the vagaries and nuances of how to work with Docker. Please let us know if you have any questions either on our forums or in the comments below.