As we reflect on what has been accomplished by the blockchain community in and look forward to I’m forced to reflect on where we are in blockchain-land.

This post is a fairly technical post which will look at two critical aspects of blockchain client design moving forward. We will cover how Eris will be approaching an increase to the modularity of our blockchain client: eris:db, as well as how we approach permissioning which is essential for properly running anything but a public blockchain.

Increasing Modularity

One of the most important aspects of blockchain-ing which we have been pursuing for a long time at Eris is the idea of breaking down the monolithic tendencies of blockchains into a more modular format.

In the Fall of Ethan and I were already telling Zach how we wanted to take a ninja sword to all of the pieces of the blockchain client.

Why? Well, in general modularity is a good thing for software design. Even amongst unichain folks (meaning, those who singularly believe that one blockchain network will become the “internet of value” and become the only ledger the world needs) there is a realization that the clients operating the network need to be built to be very modular in their design. Amir Taaki was arguing this as far back as early IIRC. Others continue to argue for the increased modularity of blockchain clients.

For those of us in the plurality of chains camp, the camp who feels that blockchains are more like databases than they are like TCP-IP and because of that do not think that the world will settle on one particular blockchain but rather that there will be millions of blockchains, for us modularity is even more important because each of these blockchains will be meant to do different things and will have very different network dynamics.

Despite the differences in philosophies between the unichain folks and the plurality of chains folks as to the blockchain networks, when it comes to blockchain clients and modularity, this is something where we can, and should, all agree. This being blockchains, the most religious software camp I’ve ever seen, I’m not going to hold my breathe for consensus here. But I do feel that all of the community can benefit from it.

Blockchain Clients Now

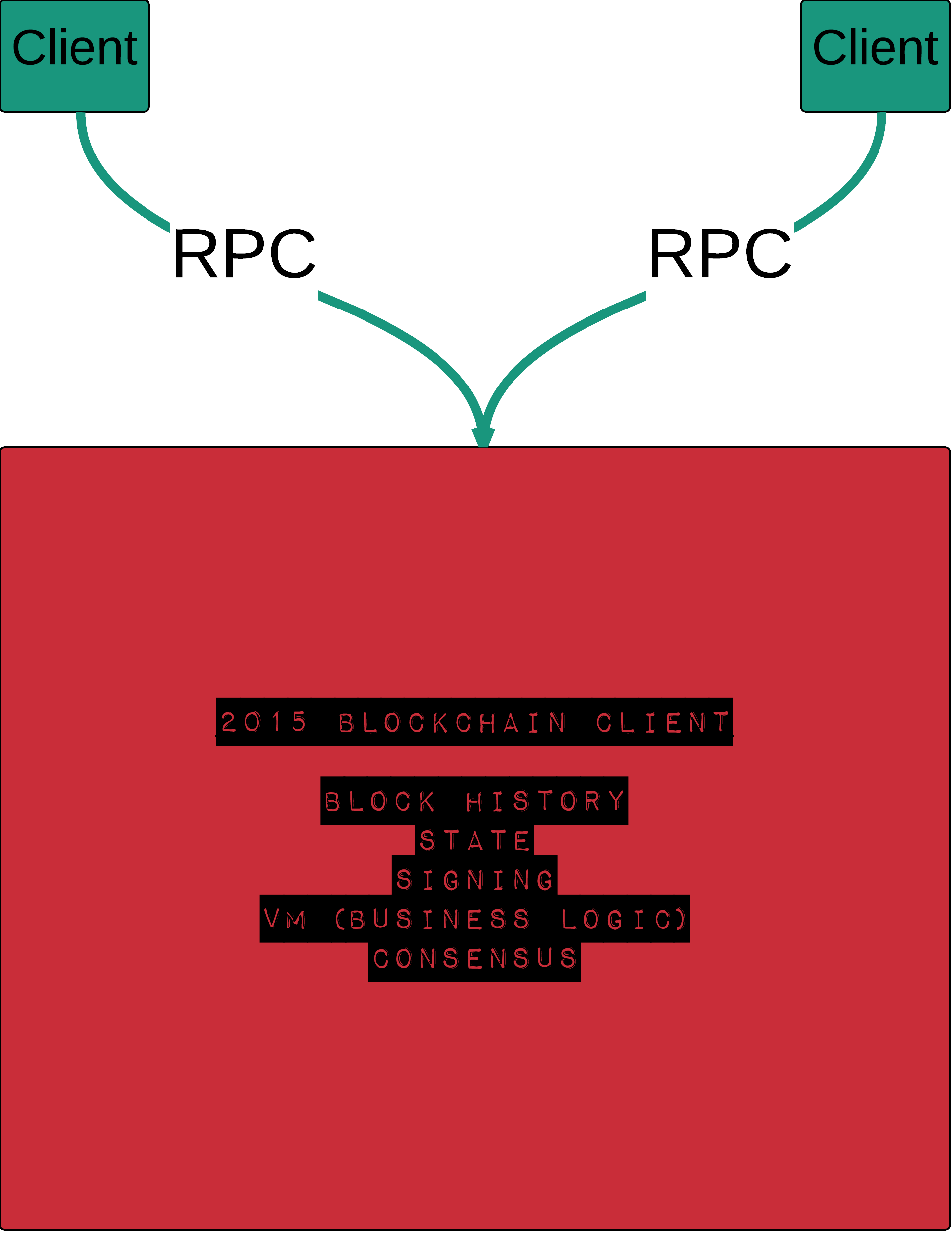

Let’s look at a typical blockchain client as currently conceived from a functional point of view.

Almost every single blockchain client runs as a singular process which is usually RPC-ed into by its “clients” (meaning middleware or frontends which need to connect into the blockchain client itself). The single process typically will be responsible for managing a whole range of activities including what I call the big three, namely:

- Signing (meaning, transactions which come in via the RPC, and blocks mostly, but also other things depending on the blockchain client in question);

- Business logic (meaning, verifying signatures, running through the “features” portions of the blockchain client, or in a smart contract enabled blockchain, running through the “smart contract machine” or VM); and

- Consensus logic (namely coordinating with other blockchain clients within the blockchain network to ensure that the world state of data amongst all of the nodes is kept in sync, resolving forks according to a pre-programmed fork choice rule, and performing a few other functions necessary at the consensus level).

Blockchain clients are also responsible for maintaining the history of blocks locally as well as building up the “state” (namely, what the data “is”).

Where We See Blockchain Clients Going

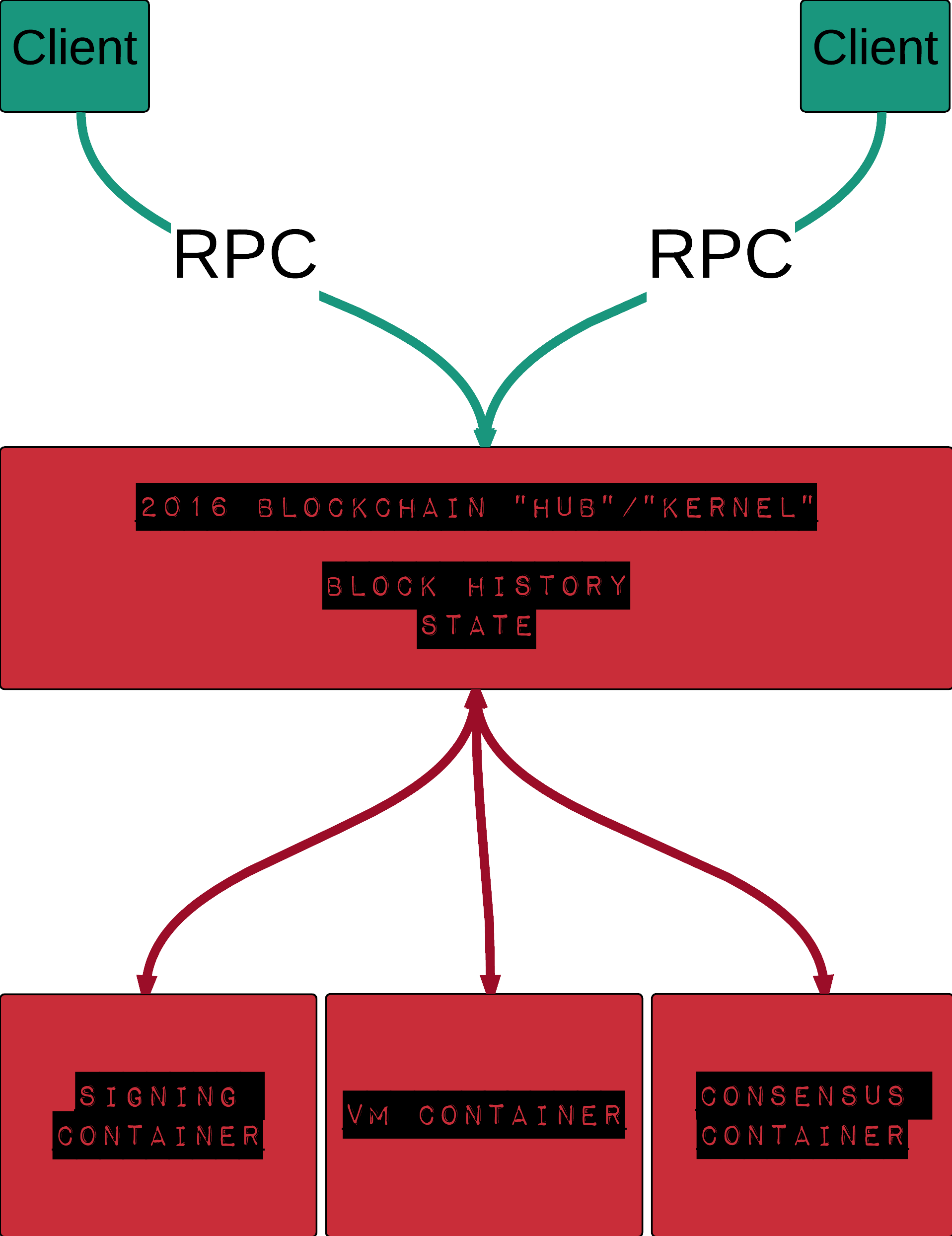

I referenced above the “big three” because these are the three portions of a blockchain client which I think are candidates to move away from a core blockchain client platform. In other words, what we at Eris are hoping to achieve is a blockchain client which looks more like this:

What we will be doing in is working to move the “big three” into their own container instances.

Signing Container

Work has already been well underway to move signing into a standalone signer. The advantages here are clear. In order to enable as wide a range of possible application configurations for which eris:db can support we need to think of signing as happening not within the blockchain client, but rather within a standalone signer. The standalone signer should be booted and available to the core node (or, as we are moving towards calling it, “the kernel”).

This opens up a great amount of flexibility because, for example, users can move their signers into HSM modules or in other highly secure zones of their data centers whereas the rest of the blockchain client need not operate in such a location.

Moving signing out of process also opens up the playing field as we move into a stage of worrying about hardening cryptographic protocols against quantum computing. It means that blockchain designers such as eris, or the bitcoin core developers, or the ethereum core team (such that it currently is) can move away from having to reinvent cryptographic protocols (which is never a good idea, and to be clear very few currently do this) as well as necessarily determining which cryptographic protocols are used by the signing (as long as the VM container, dealt with below, knows how to verify signatures; and the consensus container, also dealt with below, knows as well).

The added modularity here means that specialization in cryptographic protocols can be isolated and managed by those who understand the intricacies of such matters without having to impact those who are interested in understanding how application states work, or how consensus operates.

Consensus Container

Work has also been well underway for us to move consensus into its own container. This will allow us to build a blockchain client with “pluggable consensus”.

We aren’t the only ones moving in this direction. It is likely that, due to the complexity of Casper, that most of the ethereum clients will move to an out of process “consensus engine” where one authenticated Casper engine (as we understand it, to be built in Scala) is utilized out of process as a standalone container by ethereum clients. One could also think of the delegated witness project within the bitcoin community as moving in this direction, although it is a different system than what we’re talking about here.

Moving consensus into its own, standalone engine, will allow eris:db to, for example, allow users to utilize a Casper consensus engine, a Tendermint consensus engine, or any other consensus engine which will fulfill the interfaces we put within eris:db. This is will give users a very powerful methodology for running different consensus engines when necessary to connect into different blockchain networks.

Stemming from the Thelonious days (which was one of our very early efforts in the direction of separating out consensus) we have always been interested in opening up the space for consensus research to happen and moving consensus into its own engine which is utilized by the “blockchain kernel” will move us fully in that direction.

Virtual Machine Container

We have not yet begun, but intend to move toward the final out of process containers of the “big three” moving the business logic of a particular blockchain network into its own container. This will allow for both “generalized” smart contract machines, such as an ethereum virtual machine or other metered virtual machines we are aware of, as well as more “packaged” solutions, such as blockchains which have hard coded “features” or require faster, native based logic mechanisms.

Moving the VM into its own engine will not only open up the playing field significantly for a broad range of smart contract based solutions, but it will also lessen the reliance upon the vagaries of the smart contract programming languages which are currently still very immature because business logic will be able to be built in a wider variety of languages than only the current (quite limited) range of smart contract programming languages.

Blockchain Clients, Reconsidered

This modularity, taken together, will dramatically open up the space for specialization and innovation within the various modules without requiring drastic overhauling of a single blockchain client.

What is the best metaphor for what we see blockchain clients becoming? We see blockchain clients themselves being akin to what in the linux world are called “distros”, or distributions. Distros are opinionated, but flexible, packaged mechanisms which allow users to leverage the linux kernel, along with a range of very low level primitives that are added together to formulate a cohesive operating system.

Distribution owners work to ensure that all of the isolated packages work flawlessly as a collective. This is where we, as Eris, will be putting our efforts as we work to refactor eris:db over the coming months and thereafter.

Who, then, will build the “kernel”? We hope, these folks.

Permissioning Properly

Lots of movement has happened over around the idea of less than fully public blockchains. No matter what we call them, less than fully public blockchains require a permission module in order to operate properly.

But where does one’s permission module reside (in a VPN? using some middleware? in the blockchain’s VM?) is a crucial question as more and more enterprises come online using permissioned blockchains.

A Background Story

Folks that know me, know that I used to be an infantry officer in the United States Marine Corps. During that time, I had the interesting “pleasure” of being present in the square in when this happened:

It was a very interesting time. An incredibly difficult time actually. While the few hours in the square when the statute was getting pulled down was a moment of communal celebration (at least for those in the square), the rest of Baghdad was an utter clusterf*ck. Prisoners had been released, old scores were being settled, banks were getting robbed, an absolute mess.

The way that we dealt with this was by taking our zone and subdividing that zone into various levels. Within each subdivided area we had folks from our unit who were in charge of specific zones. They were out in the community operating with the people.

As Marines, we had been constantly trained in how to deal with very fluid situations. At the time we called this the “three block war” where in a single patrol you can go from: (block 1) humanitarian efforts to (block 2) peacekeeping efforts to (block 3) combat efforts all in a very short amount of space and time. We were also trained to be ruthless when we need to take action of the combat variety, but otherwise to have empathy for what was happening around us.

Taken together this gives Marines a particular reputation within the military. When the situation is volatile, Marines are what you want. But we don’t have the formalisms and sheer numbers that were required to “police Baghdad”. So the decision was made that we would not stay in Baghdad and would be replaced by units from the US Army.

When we were handing over our areas to the Army unit that was replacing us, friends and I gave our replacements a “tour” of the zone. Pointing out houses we had been watching, introducing elders and other power brokers we had met, etc. Generally giving them the lay of the land. But the replacements didn’t want meet any of these people or to see any of the suspected areas. They simply wanted to know where was the “base”; where was the safe zones. These questions were antithetical to us in the Marines who are trained to operated not from “safe zones” but wherever we currently were.

Our training had given us the confidence to integrate with the community. We knew that when push came to shove if we needed to fight we could. But we also knew that what we were there to do was much more complicated than simply fighting and what was essentially required was that we be as integrated into the community as possible.

We left. Things went south (for a whole host of reasons I’ll leave to historians).

Fast forward. I was visiting Aspen where I had lived for a while between the Marines and going to law school and I watched a film with friends. It was a hippy film where a musician had gone to visit Baghdad at the height of when things were bad ( was the visit IIRC). One scene in particular stood out to me. The musician asked his cab driver when things had “gotten bad” in Baghdad. His answer will stick with me until the day I die:

Well, when the Marines were here things were actually OK. They were integrated into the community, they were not scared of us, they treated us like, well, human beings. But when they were replaced by the Army everything changed. Suddenly the Americans became scared, they weren’t integrated into the community, and they treated us all like enemies.

What the hell does this have to do with blockchains? I’m getting to that just now.

Permissioning Blockchain Clients

When we put an unpermissionable blockchain client behind a VPN we can achieve some level of permissionability. The problem is that when we run blockchains in this manner, we’re really forced to “find the base”. This is because when you take a blockchain client which does not have a permission module built into the client and you try to make a permissioned blockchain network with it then you are forced to rely upon the “base” of the VPN. The “safe zone” if you will.

There is an oft cited critique of permissioned blockchain networks that they are less secure that public blockchains due to their lower hashing power. This critique holds only under the following scenario: where you have a blockchain client that does not have a permission module, is POW, and a significant amount of hashing power is able to get behind the VPN. Outside of that scenario, the critique as an attack says more about the knowledge level of the attacker than actually communicates something important. If an enterprise has taken a POW based blockchain without a permission module and properly runs it behind a rock solid VPN then the critique is misplaced.

Yet, and here is the critical point from our point of view at Eris, that enterprise who had taken a POW based blockchain client without a permission module and ran it behind a VPN, is making its blockchain clients operate like the Army officers in the above story. These blockchain clients are susceptible to attack if they are not “inside their base”. As such, they lose a good amount of their utility.

A VPN v. A Permission Module

eris:db is a blockchain client which has a built in permission layer, still one of the only such blockchain clients currently in open source. We have designed eris:db to “go into the wild” rather than to “go to its base”. Because of the rock solid, granular, key-driven, capabilities-based permission layer built into eris:db, these blockchains are meant to easily operate outside a VPN without having to worry about mining attacks or other attacks which would mess up the operational consensus.

This is an incredibly important difference because one of the main benefits of blockchains (in our view) is to provide increased verifiability over business processes that cut across stakeholders and in order to achieve that VPNs likely will get in our way. Perhaps not at first during the experimentation phase, but eventually they will certainly get in our way.

With an eris:db chain we use key-driven permissioning which means that the same key you use to sign whatever interactions you are sending to the blockchain network also determines your level of permissions (assuming the permission layer is active for a given blockchain network; it can be turned off when it gets in the way). This increases dramatically the overall, systemic verifiability vis a vis having two analog systems which need to operate in parallel (the key-based blockchain network and the usually password-based VPN).

Let’s say an organization begins with their blockchain network behind a VPN but uses an unpermissioned blockchain. Over time, as the contracts are stable and as the enterprise wants to increase the access to the other stakeholders involved in the process, the organization decides that it wants to open up the blockchain network to a wide variety of other participants with various levels of permissions. In order to do that the VPN would become so riddled with exceptions and access points as to no longer really be doing its job. And that VPN overload would be simply because the blockchain client chosen did not have a proper permission layer built in that would allow the blockchain client to “go out into the population” like my fellow Marines had done in Baghdad.

On the other hand, take the same exact system and change out the blockchain client to one which has a permission layer and when the organization seeks to open up the blockchain network to a wide variety of participants it can simply not run the network behind the VPN any more and send simple, verifiable, and transparent permission altering transactions to the blockchain which will open up various capabilities of the chain.

What do you see happening in blockchains going forward? Let us know in the comments.

(Photo credit: CC-BY: David Luders)